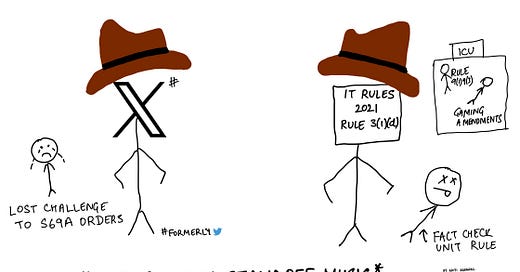

Edition 6: Now X (ex-Twitter) is challenging IT Rules 2021

X, formerly Twitter, wants Karnataka HC to strike down Rule 3(1)(d) as unconstitutional and ultra vires of the IT Act. It also wants I4C's Sahyog to be declared at least ultra vires of the IT Act.

A big part of me thinks that IT Rules 2021 are cursed.

At least 17 petitions — from Big Media, small media, individual journalists, Big Tech — across the country have been filed challenging parts of the rules, so much so that the only unchallenged parts of the rules are the title and arguably, the definitions.

Part II (rules 3 to 7) governing intermediaries, part III (rules 9 to 19) governing streaming platforms and digital news publishers, and the Digital Media Ethics Code have been challenged either in their entirety or in parts.

Rule 3(1)(b)(v) — concerning the government’s fact check unit — has been struck down as unconstitutional by the Bombay High Court. (The judgement has been challenged by the Centre in the Supreme Court.)

Rule 4(2) — concerning traceability, particularly on end-to-end encrypted messaging platforms — has been challenged by tech behemoths WhatsApp and Meta in two separate lawsuits.

Rules 9(1) and 9(3) concerning the inter-departmental committee for streaming platforms and digital news publishers have been stayed.

And by MeitY’s own admission, the 2023 amendments related to online gaming remain “unenforceable” as the nodal ministry has not yet designated any self-regulatory body required by the rules.

And now there is a new challenger in town — X (formerly Twitter). And it is going after Rule 3(1)(d).

In a significant move, the Elon Musk-owned microblogging platform wants to expand the scope of its March 2024 writ petition that had challenged the use of Section 79(3)(b) of the Information Technology Act to issue content takedown notices and the creation of Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre’s (I4C) Sahyog portal meant to “streamline” takedown notices sent under the section.

In its March petition filed before the Karnataka High Court, X only wanted two things from court: first, declare that Section 79(3)(b) does not allow the government to issue blocking orders; and second, protect X for not joining I4C’s Sahyog and for not complying with notices issued through it.

Now, X wants the court to strike down Rule 3(1)(d) by declaring it unconstitutional for being ultra vires (exceeding the remit) of the parent act. Or at least read down Rule 3(1)(d) to declare that it does not grant the state any blocking powers.

And for the court to declare that Sahyog is ultra vires of the IT Act “and/or” is unconstitutional.

The Tech Trace has seen X’s amendment of petition, filed on May 30.

What is Rule 3(1)(d)? Rule 3(1)(d), read along with Section 79(3)(b) of the IT Act, allows notified authorised agencies to send takedown notices to intermediaries which must be complied within 36 hours. I recommend reading my article on these two provisions here.

By allowing takedown notices to be sent for violation of “any law for the time being in force”, Rule 3(1)(d) exceeds the restrictions on free speech listed Article 19(2), X has argued. This exceeds the ambit of Section 69A (blocking provision of the IT Act) both in isolation and as per the safeguards laid down by the Supreme Court in the 2015 Shreya Singhal judgement.

X’s main argument is that Section 79 is an exemption provision, that is, protects an intermediary from liability for third party content provided certain conditions — laid out in IT Rules 2021 — are met. It is not a provision that grants the government or law enforcement agencies power to issue blocking orders, which remains solely within the ambit of Section 69A, the platform said.

By allowing any “authorised agency, as may be notified by the Appropriate Government” to issue the takedown notices through Rule 3(1)(d), X argued that it empowers “countless executive officers to censor information”. Both — the reasons for blocking and people ordering the blocking — thus exceed what is allowed by the IT Act.

Against Sahyog, called “Censorship Portal” by X, the platform has argued that it is not backed by law and creates a quasi-judicial process led by the executive which unilaterally decides on the lawfulness of online content.

Why X thinks Rule 3(1)(d) is unconstitutional

1. Violates Article 14 and 19, Shreya Singhal judgement

Rule 3(1)(d) allows takedown notices to be issued for any content that is “prohibited under any law for the time being in force”. This, as per X, expands the restrictions placed on free speech under Article 19(2).

X argued that in the Shreya Singhal judgement, the Supreme Court had upheld Section 69A but read down Section 79(3)(b) and Rule 3(4) of the repealed IT Rules 2011 (which were superseded by 2021 rules). It had held that any unlawful act beyond Article 19(2) cannot be a part of Section 79.

The SC had read down “actual knowledge” of the repealed Rule 3(4) to mean a court order.

X has argued that since Section 79 was not amended after the Shreya Singhal judgement, Rule 3(1)(d) cannot overrule the said judgement which remains the law of the land and thus the executive cannot issue takedown/blocking orders outside of Section 69A.

2. Over broad provision like the struck down Section 66A, Rule 3(1)(b)(v)

Comparing Rule 3(1)(d) to the now struck down Section 66A of the IT Act, X said that the rule gave the government “unfettered, unguided, disproportionate and arbitrary powers” to order removal of “vague classifications of information that they deem is ‘unlawful’”.

Section 66A — which criminalised online speech that was “grossly offensive”, “menacing”, “knowingly false”, “causing annoyance or inconvenience” — was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in its 2015 Shreya Singhal judgement for being vague and overbroad, and for potentially impinging on protected and innocent speech.

X argued that Rule 3(1)(d) is similarly wide and vague, lacks safeguards, and goes beyond the grounds specified in Article 19(2) and Section 69A.

Rule 3(1)(b)(v) — the fact check unit amendment — was struck down as unconstitutional by the Bombay High Court for similar reasons, X submitted.

3. No prescribed procedure

Much like with Section 79(3)(b), X submitted that Rule 3(1)(d) has no procedural safeguards, judicial standards or other “objective criteria” to determine if information is “unlawful”, making it unconstitutional. There are no safeguards to protect fundamental rights in the rule.

The process to issue blocking notifications is not defined. There is no mandatory periodic review of the government’s blocking order under this provision. As the blocking orders under this rule are not time-bound, they are disproportionate, X said, resulting in “permanent censorship” on the basis of “a mere allegation” about the illegality of the information.

Citing takedown notices issued on “unsustainable grounds” by by Railways Ministry (details available here and here), X said that the lack of procedure had already been “abused by executive officers”.

X said that the Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of Section 69A in Shreya Singhal only because the process has multiple procedural safeguards.

Like Section 79(3)(b), X argued that Rule 3(1)(d) creates a parallel blocking process outside of Section 69A and the related 2009 Blocking Rules without any of the safeguards prescribed there, violating Article 14 and the IT Act.

As a result, the same content (such as that affecting public order) can be blocked under two mechanisms — one with safeguards (Section 69A) and the other without (Section 79(3)(b) read with Rule 3(1)(d)).

4. Too much power to the executive

X argued that Rule 3(1)(d) “empowers executive officers to censor any information without following any stipulated procedure or safeguards”, granting them “limitless unchecked authority to censor online content”. This makes them “arbiter” of permissible speech “to censor content” in violation of Section 69A.

The disproportionate and “unguided power” to countless authorities in violates Articles 14 (equality before law) and 19 (fundamental rights), X said.

So many empowered executive officers!

X, echoing its arguments against Section 79(3)(b) and Sahyog, said that notifications issued under Rule 3(1)(d) permit “countless executive officers” to issue takedown notices beyond the scope of Article 19(2). It accused MeitY of “impermissibly” expanding the scope of Article 19(2) by seeking all central ministries and “countless state agencies” to notify nodal officers under these provisions.

The platform said that it learnt about some of the notified nodal officers — such as those notified by the Ministry of Heavy Industries and the Ministry of Rural Development — only after the Centre filed its statement of objections on March 27. The platform wants these (along with state level notifications) to be quashed along with notifications from the ministries of home, defence, railways and finance.

The Ministry of Heavy Industries, in an office order dated November 9, 2023, appointed a senior official from the National Informatics Centre (NIC) in MHI as the nodal officer to issue takedown notice under IT Rules. Seeking to get it quashed, X submitted that NIC is a part of MeitY, not MHI. This, X argued, shows lack of application of mind in issuing these notifications as MHI empowered an officer who reports to MeitY and is not “intimately” connected with the functioning of MH. X argued that it shows that the notifications are “not issued to combat unlawful information” of the MHI but to “achieve the goals of MeitY to circumvent Section 69A”. This allows MeitY to control blocking orders issued in the name of MHI, the platform said.

Content originators excluded

Rule 3(1)(d) does not notify the originator of the content of the takedown notice or give them a chance to be heard. This violates principles of natural justice and Article 14 (equality before law), X said.

Since the notice about the unlawful content only needs to be sent to the intermediary, and the intermediary must comply with such a notification within 36 hours to retain its safe harbout, it “effectively preclude[es] any legal challenge to the notification prior to censorship”, X said.

To be sure, loss of safe harbour is a determination that only courts can make, not the executive. Safe harbour is not a medal that is awarded by MeitY or MIB or the police; it is something that an entity automatically has by virtue of the function it performs and is limited to that particular intermediary function. Thus, I don’t have safe harbour for the content of the newsletter that is delivered to your inbox but I automatically have it for the comment you may post on it. Read what it means to lose safe harbour here.

5. Usurping judicial function by deciding what is lawful

X submitted determining “lawfulness” of content is a judicial function. Only courts can decide whether a restriction/prohibition on speech is the least intrusive measure and if such restriction is proportionate to the claimed benefit.

By letting executive officer determine what is unlawful, X says that the government is violating the doctrine separation of powers. Rule 3(1)(d) notices are issued without any court proceedings or judicial determination of the lawfulness of content, thereby making the executive the “final arbiters of the lawfulness of information”.

“Rule 3(1)(d) unlawfully circumvents this judicial process,” X said.

This circumvention means that Rule 3(1)(d) violates Article 14 because it allows for “summary removal” of electronic information. This is not allowed for printed material such as books, X said.

6. Usurping legislative function

X argued that the rule exceeds the government’s rule-making power because it makes a law that Parliament never intended. “MeitY has usurped legislative powers by passing Rule 3(1)(d),” X argued as only the parliament can exercise “essential legislative function”. It said that as per constitutional limitations and standards, a delegate (rule-making body) cannot have more legislative authority than the delegator (parliament).

7. Threatening safe harbour means intermediaries will censor

X submitted that since Rule 3(1)(d) “threatens” intermediaries with loss of safe harbour under Rule 7 and potential penal action, intermediaries will obey takedown directions leading to “direct censorship”, violating the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) of Indian citizens.

X said that this creates “a coercive environment of censorship, driven by fear of potential liability to intermediaries”, causing a chilling effect on free speech.

The platform cited the Bombay High Court’s judgement to strike down Rule 3(1)(b)(v) as unconstitutional where the court had observed that an intermediary would “bend the knee to a government directive” about content to retain its safe harbour, thereby directly threatening users’ free speech rights.

Executive performing judicial function: X now wants Sahyog to be scrapped

Continuing to call Sahyog the “Censorship Portal”, X submitted that the portal creates a quasi-judicial process through which any executive officer — either at central or state level — can “unilaterally adjudicate” the lawfulness of information and direct its removal, thereby performing a judicial function.

X said that the portal has no judicial members to adjudicate the lawfulness of information and as an adjudicatory body, suffers from lack of impartiality and independence.

The personnel notified for Sahyog via Section 79(3)(b) notifications are executive officers — such as police personnel, railway officers, GST officers, etc. — who are appointed by the government at its will, X said. They lack security of tenure and are thus subject to the government’s “unbridled discretion”

As it sought a decree seeking Sahyog’s unconstitutionality, X again submitted that the portal is not backed by law and is ultra vires of the IT Act. The platform said that the Centre recognises the digital portals need statutory backing which is why the CGST Portal, NSE Electronic Application Processing System (NEAPS), etc. are codified in relevant laws and regulations.

The platform said that process for Sahyog was being developed “capriciously, as an afterthought and without any legislative support” to “control information on the internet”. It also said that the Sahyog process was an “opaque and clandestine” process mean to restrict speech as the orders were only sent to intermediaries. It said that there was no reason for not making these orders public.

X also argued that the MHA was precluded from creating such a portal due to the doctrine of occupied field (that is, executive power cannot be exercised in a field which is already governed by laws made by the parliament) as information blocking is fully governed by Section 69A and the related 2009 Blocking Rules, and intermediaries’ obligations are already governed by IT Rules, 2021.

“The End”

This is very helpful!